Diagram 1

Diagram 2

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

St. Francis of Assisi came to Arezzo in the early years of the 13th century and found a city torn with internal strife. With one of his many miracles, Francis brought peace to the community and blessed it with the vision of a great golden crucifix spreading its arms across the sky. As a result, his friars were allowed to congregate in a small community outside the walls and preach their message of love and salvation.

By the early fifteenth century, the Franciscan friary had moved into town where it built an imposing church dedicated to its founder. The apse end, rebuilt after a fire, was awaiting decoration. It was the custom in such establishments--always in need of financial support-- to lease out space within the buildings to families to use as burial grounds. This privilege brought the friars monetary contributions for upkeep and/or enhancements of paintings, sculpture, and other church furnishings. The chapels on either side of the main apse had already been painted in the late 14th century, but the chancel itself, the Cappella Maggiore, which had been leased to the local Bacci family, was still without decoration.

After complaints from the friars in the 1440s, the Bacci sons sold a vineyard and other real estate to acquire the cash to begin paying for a campaign of fresco painting. As was usual, the administrators of the church, the Franciscans, were the ones who chose the appropriate subject matter, in this case, a subject dear to St. Francis's devotion to the cross of Christ, the Legend of the True Cross. The apocryphal narrative was set on the three vertical walls of the chapel, with paintings on the triumphal arch and the vault creating a scheme of redemption under the authority of Papal Rome. Bicci di Lorenzo, an aging artist from Florence, was hired to do the work, and he and his workshop started at the top (frescoes are always painted from the top down because of dripping), and completed the Last Judgement high up on the entrance arch, and the four Evangelists on the webs of the ribbed vault. Sometime during this operation, Bicci di Lorenzo grew ill and returned to Florence where he died in 1452. Members of his shop continued the work for a short while, painting most of the decorations of the ribs and other structural members and at the least two standing figures of the four Fathers of the Church that are just below the vault. Then they too left Arezzo. Only after this sequence of events was Piero della Francesca called in to complete the project.

Ever since the early 20th-century when European artists took Piero as their favorite, he has gained the reputation as the one Renaissance painter whose calm, forceful, and supremely imposing figures could be enjoyed by everyone without regards for their religious content. His high-toned colors, his geometrically perfect forms and spaces, his mesmerizing light flows and volumetric shadows satisfied the current visual hunger for simplicity, purity, and strength. In this vein, one critic even called him "the first Cubist". In the 15th century, however, it was a different matter. Piero's work, like that of almost all mid-15th century artists, served a religious purpose. As a result, there is no separation between what he represented and the way he represented it, between his form and his content. Moreover, while he was recognized as a maestro of painting, he was also honored as a great mathematician. The three important treatises he wrote (on algebra, geometry, and perspective for painters) are acknowledged as among the most important of his time. These interests are reflected in his paintings and may, to some extent, explain his appeal to the modern eye.

In spite of his current fame, it is somewhat surprising to find that there are no documents recording his Arezzo commission. We do not know when Piero was engaged (only that is was after 1452). We do not know what he was told to do (only that it was to paint the Legend of the True Cross, a subject used in many other Franciscan churches). We do not know who or how many men worked under him (although at least the name of one assistant, Giovanni di Piamonte, is knows from other sources). And we do not know when he finished the job; we know only that in 1466 the frescoes were referred to in the past tense, and so we may assume that they were complete. Thus all the information we have comes the frescoes themselves. And they are some of the most challenging paintings of the Early Renaissance.

THE LEGEND AND ITS DISPOSITION:

Diagram 1 |

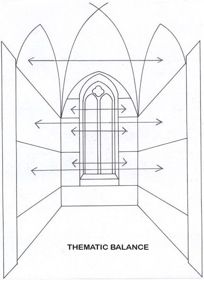

Diagram 2 |

|---|

One of the most demanding aspects of the cycle is the way Piero arranged the scenes on the walls. Although the story of the Cross is of longue duré ---a compilation of medieval legends beginning in the time of Genesis and progressing to the 7th century A.D.---it follows a simple chronological sequence. One might expect such a narrative told visually to "read" like pages in a book, that is, to start on the left at the top; move from left to right, and proceed down the walls, tier after tier. Piero chose not to tell the story in this manner, but to rearrange the sequence in a dramatic way. He placed his Genesis scenes not on the left, but on the right wall at the top and made them read "backwards" from right to left. He put the next episodes on the second tier and reversed the order to read left to right. He then had the story jump to the second tier of the right side of the altar wall and progress diagonally down to the lowest tier on the left side, and so on. Diagram 1 shows how the "Narrative Sequence" continues in this "irregular fashion," ending, not at the bottom but at the top tier of the left wall!

The legacy of Piero's "rearranged" chronology has two parts:

1) Jumping around the space reminds one of the chaotic rhythms of a medieval romance; the Romance de la Rose, for example. Such stories, which apparently St. Francis loved when he was a boy, are full of adventure with stalwart knights and ladies fair, and always a moral overtone and religious goal. Their structures are full of surprising stops and starts, changes of directions, and what the modern mind considers to be irrational time changes. The Legend of the True Cross, as it developed, came out of this very tradition, and Piero did not want his viewers to forget this fact.

2) At the same time, the arrangement makes the story take on another character, one that is abstract in nature and serious in its implications. The two lunettes at the top of the side walls match, showing the beginning and the end of the story, each centered in the wood of the cross. The second tiers match; they express the power of royal women who are divinely inspired to recognize the holy wood. On the altar walls, the top tiers show matching prophets; the second tiers represent comic relief with serious undertones. The bottom tiers also match. Both are scenes of annunciation: one of the birth of Christ, the other the birth of Christianity. The bottom tiers on the side walls match. They are battles scenes. One is a bloodless victory over fellow Romans at the sign of the cross, and the other is a bloody battle for victory over the blasphemous infidels. Diagram 2 shows the "Thematic Balance." The new arrangement produces the effect of symmetry and balance, gravity and dignity required by Aristotle and Horace for creating epic poetry. By dint of his re-organized disposition, Piero achieved what might be called the first modern epic.

This page presents the fresco cycle's "pattern of disposition" in the traditional manner, that is, with diagrams. The benefit of the Interactive Computer Model is that the viewer can move through the space of the chapel not only viewing the paintings in detail but also following the sequence(s) as Piero conceived them. Remember, he never had a chance to see the frescoes in this manner. While he was working, the chapel was full of scaffolding and he would have had no way to step back for a general view. And even Piero couldn't fly.

MAL